The Rough Notes Company |

|

|

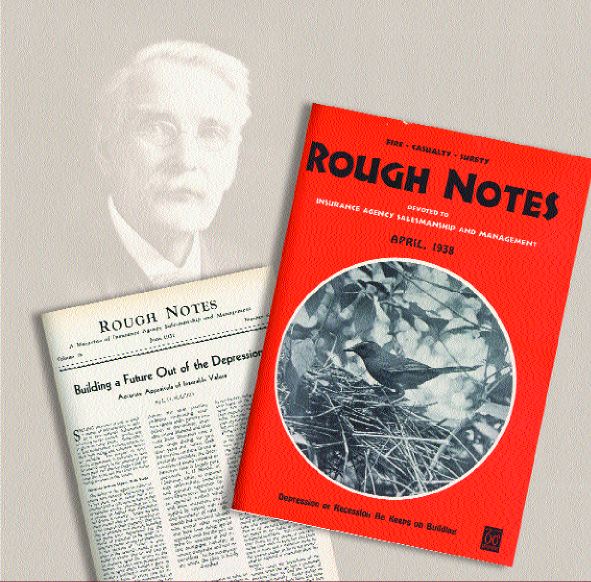

The beginning of the 1930s found the country still reeling from the 1929 stock market crash. Railroad cars were filled with the homeless, and the refrain "Hey buddy, can you spare a dime?" was heard throughout the country. After being elected president in 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt authorized a moratorium on banking, and the Social Security Act became law. Al Capone was found guilty, and Amelia Earhart's plane was lost in the Pacific on July 2, 1937. The Depression was on the mend by 1934, and the nation's confidence began to rise. Then in 1939, Germany shocked the world by invading Poland. |

|

|

As the Great Depression brought harsh conditions to the country, |

Rough Notes magazine was filled with articles on "Business Getting Ideas"; many of the editorials advocated "Churches as good prospects for fire insurance," "Nearly Every Church Having Fire or Loss from Windstorm Reveals a Bad Case of Under-Insurance," and "Before another week passes, learn as much as you can about your own church's insurance protection and be governed by your action by whatever you may thus learn," (RN editorial 1930). Another editorial promoted "Laundries as Insurance Agency clients." These editorials were designed to give agents specific ideas on how to approach a client about a specific risk. Principals appreciated this effort and would often purchase article reprints to help motivate and educate their agency's sales force. In 1926, The Rough Notes Company acquired Insurance Pictorial, a publication that provided advertising helps to agents. Insurance Pictorial grew so rapidly and became so successful with agents that Rough Notes decided to apply the same photo realism technique to life insurance and created a sales magazine called Estate-O-Graph. Because telling the insurance story through photographs proved to be one of the best selling tools for agents, Rough Notes created yet another publication called Life Pictorial, a magazine geared towards policyholders. At the height of the Depression, the publication's name was changed to Conservation Pictorial, and its size was decreased to make it small enough to be sent in the mail along with premium notices. This cut agents' cost for postage and made the magazine's photo reproduction process more economical. RN went one step further for its agents and started using a new color of ink--Aquatone--to catch policyholders' attention. RN acquired exclusive rights for the life insurance field from Edward Stern & Company of Philadelphia, the license holder for Aquatone photo reproduction. |

During the Depression, life insurance fared much better than property and casualty. Life insurance was considered a safe investment for a family of limited means, and many insureds were able to take policy loans against their life insurance. Life policies contained clauses that provided regular payments for disability, and many insureds took advantage of this clause. The property and casualty insurance companies saw millions of dollars in losses after the stock market crash and many solid P&C companies were on the edge of closing their doors. The collapsing banking system only exacerbated the situation, throwing more people out of work. However, by 1933 auto premiums began to grow as did fire insurance. |

|

|

Rough Notes Goes Hollywood One of the most exciting publications/sales kits that RN produced during this decade was SAVE (Selling Aids with Visual Emphasis). In true Hollywood style, RN's advertising department set up a photography studio with props and actors to stage situations in which an average person might need insurance. The most popular were accidents such as falling on personal property, or home burglary (by either a household staff member or a stranger). SAVE's photographic ads and sales prompts proved to be both popular with the agents and profitable for The Rough Notes Company. |

In 1926, The Rough Notes Company created an "Insurance Advertising Service" department, later called Pictorial Division, which grew to 16 employees by 1938. New initiatives were the hallmark for this department, as the staff created visual sales kits for both life and casualty. The "Zip-It Visual Sales Kit" was a leather-bound, loose-leaf book with sections devoted to each of the major uses of life insurance. This type of sales kit was also developed for casualty agents and was called "Insurable Hazards Illustrated," a complete photo manual that included all casualty lines. By 1938, agents had purchased more than 27,000 visual kits. In 1926, The Rough Notes Company created an "Insurance Advertising Service" department, later called Pictorial Division, which grew to 16 employees by 1938. New initiatives were the hallmark for this department, as the staff created visual sales kits for both life and casualty. The "Zip-It Visual Sales Kit" was a leather-bound, loose-leaf book with sections devoted to each of the major uses of life insurance. This type of sales kit was also developed for casualty agents and was called "Insurable Hazards Illustrated," a complete photo manual that included all casualty lines. By 1938, agents had purchased more than 27,000 visual kits.

All of the printing for The Rough Notes Company's magazines, forms and books, as well as publications for other publishers, was carried out at the company's own printing plant. Because the company grew rapidly after 1917, it became necessary to expand its printing facility and equipment. In the early 1930s, RN invested in the latest high-efficiency technology so that its own plant could print 100% of its volume. The investment paid off because RN could then print in two colors and put the publications on a controlled schedule, which resulted in lower costs. In 1938, more than a million magazines went through its high-speed presses, and nearly 1.5 million circulars and pamphlets were published, many of which were in two or three colors. Moreover, some 4.5 million forms for the 4-in-1 Billing Unit came off these presses.

|

|

|

During the Depression, life insurance fared much better than property and casualty. Life insurance was considered a safe investment for a family of limited means, and many insureds were able to take policy loans against their life insurance. Life policies contained clauses that provided regular payments for disability, and many insureds took advantage of this. During the Depression, life insurance fared much better than property and casualty. Life insurance was considered a safe investment for a family of limited means, and many insureds were able to take policy loans against their life insurance. Life policies contained clauses that provided regular payments for disability, and many insureds took advantage of this.

The property and casualty insurance companies suffered millions of dollars in losses after the stock market crash and many solid P&C companies were on the edge of closing their doors. The collapsing banking system only exacerbated the situation, throwing more people out of work. However, by 1933 auto and fire insurance premiums began to grow.

|

|