|

|

|

|

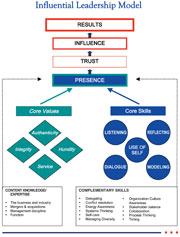

Perspectives on Management Influential leadership Success in reaching sales goals can depend on a leader's reaction to employees' questions By Hamid Mirsalimi, Ph.D., and Maureen Hunter, Ph.D. Editor’s note: What are the various ways in which you serve as a leader in your organization and in your private life? Leadership is not something that only a few at the top engage in; individuals at any level of an organization can assume such a role. When you don’t wait to be told what to do, but think about what needs to be done; when you think outside the box and influence others to do the same; when you think creatively and bring others on board with your vision of how something should be done; when you look into the future and think about possibilities as opposed to obstacles, and inspire others to see the future in a similar manner, you are engaging in leadership no matter where you are in the organizational chart hierarchy. So, do you see yourself as the leader that you have the potential to be? Have you embraced and given voice to the leader within you? The task is hardly to become a leader; the task is to learn to bring out the leader within you. Leadership is often defined as the art and practice of achieving desired results through others. What are those qualities that make a leader an influential leader? To begin with, let’s focus on the word influence. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, influence has to do with “the act or power of producing an effect without apparent exertion of force or direct exercise of command; the power or capacity of causing an effect in indirect or intangible ways.” Influential leadership, then, is the type of leadership that relies on influence as opposed to coercion. It is the type of leadership that creates followers who want to follow as opposed to followers who believe that they have to follow. The DBH Consulting Influential Leadership Model breaks down the components of influential leadership so that it can be utilized by everyone who is interested in being a more effective leader. The base of the model stresses that a leader needs to possess content knowledge and expertise. Such expertise may include knowledge of the business and industry, mergers and acquisitions, management discipline, and function. Followers would be hard pressed to follow a leader whose technical expertise and knowledge they don’t trust. A leader also needs to possess complementary skills. Fundamental among them are the skills of delegating, conflict resolution, energy awareness, system thinking, self-care, management of diversity, organizational culture awareness, stakeholder balance, collaboration, process thinking, and timing. While knowledge, expertise, and skills are fundamental necessities for any leader, the heart of influential leadership comes from the leader’s core values, such as authenticity, integrity and service. Influential leaders believe in the value of authenticity. That is, they are who they are; what they do is reflective of their personality and character. In his Authentic Leadership, author Bill George, the former chairman and CEO of Medtronic, says that “authentic leaders genuinely desire to serve others through their leadership. They are more interested in empowering the people they lead to make a difference than they are in power, money, or prestige for themselves. They are as guided by qualities of the heart, by passion and compassion, as they are by qualities of the mind.” Another core value of influential leaders is integrity; that is, being consistently honest, forthright, and ethical; doing what they say and saying what they do. They walk their talk. Followers need to be able to trust the leader, and without that trust, influence is impossible. Influential leaders believe in humility; they are willing to acknowledge that they don’t know everything; they are open to learning from others. Influential leaders also hold service at a high value. They want to be of value to others, contributing to the benefits of others, whether it is their employees, their business, their industry, their family, or their peers. Leadership skills Along with the above values, influential leaders develop a set of fundamental influencing skills that appear to be deceptively simple. Those skills include listening, reflecting, dialoguing, modeling, and use of self. There is an art to listening and engaging in dialogue. Think of the last time someone challenged you in a conversation. Were you truly listening? We often listen only half-heartedly. For example, if you have a tendency to formulate your rebuttal while someone is talking to you, you are not fully listening. Many problems in business occur because of poor communication, and good listening is the first step toward better communication. The skill of dialogue is also fundamental. What kind of stance do you take? Do you assume an assertive, aggressive, or passive approach? Do you engage in too much advocacy for your position? Do you engage in sufficient inquiry regarding someone else’s position? If your approach is heavily tilted in the direction of advocacy of your position, chances are you are not engaging in a good listening and dialogue process. Reflecting is another core skill that influential leaders practice. Reflecting involves taking time to become fully aware of your own mental processes—your thoughts, feelings, and reactions to various situations. Modeling, another core skill of the influential leader, involves the recognition that you are setting an example for others through your own behavior. The skill of modeling requires an awareness that your behavior is the primary communicator of your intent and challenges you to manage your behavior accordingly. Last, but certainly not least, is the skill of the use of self. This skill involves using yourself as a barometer to assess what is going on inside you and around you and how to respond to your environment. For example, do you know what your “hot buttons” are? Do you know what makes you tick? Do all of your reactions have to do with the present situation or is a portion of your reaction coming from past experiences? If you are fully capable of using yourself as a barometer, you will be able to use your reactions and decipher what reaction is due to your past and what reaction is truly a response to the situation at hand. Then you can use that information to make dead-on strategic initiatives. You must use your self as a fined-tuned instrument—no easy task! If leaders take on core values and if they develop core skills, they will walk in the world differently! That is, they will have presence, and presence cannot be acted. Presence creates a chain of reactions. When leaders have presence, followers will trust them. That trust is at the core of being influential. When was the last time you were truly influenced by someone you did not trust? You might have been influenced to go the other way, but not influenced to follow! When leaders have presence, when others trust them, and when followers are influenced by them, desired results from the team/organization will follow. That is how a leader achieves results—not by coercion, but by influence. A fictional example Consider Company X, an indepen-dent insurance agency. The CEO, a successful man in the industry, has set an agenda to increase revenues five-fold in the next five years. He believes that such an expansion is possible, while the employees—from producers to account executives to administrative personnel—believe that such an expansion is nothing but a pipedream. What often happens in such situations? To begin with, some brave souls may express their doubts. How is the CEO going to hear the concerns? A CEO who truly knows how to listen will ask questions, pay attention, and will try to see the logic of those who doubt the plan. A CEO who is reactive, who deep down inside possibly equates any doubts about the vision with subversion, listens half-heartedly and tries to come up with a rebuttal. He or she does not ask many questions but, instead, advocates heavily for his or her position. Because of that positional power, others might quickly sense that disagreeing with the CEO is not safe and probably will hesitate to express their concerns. They will pretend to be doing what is asked, but in reality they will be dragging their feet. Precious time passes while the CEO believes that the employees are all in line with the vision. When it finally becomes evident that the desired results are not going to be achieved, the CEO becomes angry, takes that anger out on the employees, becomes frustrated and finally creates a new agenda with a new set of goals. Those who report directly to the CEO then model the CEO’s style. They too become angry with their employees. Those employees try to voice their concerns and find themselves faced with a manager who cannot listen. They feel unsafe, so they pretend that they are in line with the new vision, while at the same time dragging their feet. And the scenario continues—on and on and on. Another example Now, consider a different possibility for Company X. As an influential leader, the CEO sets the same agenda: five-fold revenue increase in five years. The employees voice their doubts and concerns. This CEO asks a series of questions aimed at increasing his understanding of the employees’ concerns. Some of those concerns prove to be legitimate. For example, employees might be concerned as to whether or not there are plans for expanding the infrastructure along the way. Being able to use himself as a barometer of how others are feeling, the CEO senses that the opposition may also have to do with the employees not knowing why such an expansion is necessary. Sitting back and reflecting on how he might feel if he were in his employees’ shoes, the CEO goes back to them and engages in meaningful dialogue about why such an expansion is necessary. For example, perhaps he has reason to believe that without such an expansion, their organization is going to lose its independent status and will be sold. The CEO communicates those concerns and helps the employees consider what is desirable about remaining independent. Thus, he communicates his value of service, letting his employees know that service to the organization, including his employees, is at the heart of his new vision. He also demonstrates humility by letting his employees know that he values their opinion, that there may be issues that he has not considered, that suggestions from others possibly could serve the entire organization. He therefore encourages open dialogue about how the goal can be achieved. Sensing his humility and authenticity, the employees model his behavior. They, too, communicate with their direct reports that they are interested in their employees’ ideas and suggestions. With employees who trust him, this CEO is much more likely to realize his vision. Becoming an influential leader is a life-long goal that requires conviction, patience, practice and dedication. * The authors |

|

|||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||