|

Agency Financial Management

Knowing when to "fold 'em"

Selling your agency now versus "waiting for better conditions"

By Kevin W. Smith, CPA

In the words of country music star, Kenny Rogers, "You got to know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em." The concept sounds simple enough. And the lure of being an expert or successful in something appeals to a large portion of us, especially when the end result of being correct is financially lucrative. If you need evidence of that, just look at the rise of the World Series of Poker over the last several years, or the prominence of day trading over the last couple of decades, or speculative real estate deals. The list could go on for quite a while, and for every success, there would be offsetting failures.

If you bought real estate in California or south Florida in the early 1990s (or ideally, before then), and you sold in the mid-2000s, you might consider yourself a real estate baron. If you picked up a parcel in mid-2008 and are still holding onto it, it is doubtful that your net worth is the same as it was prior to the purchase, assuming all else being equal.

The same could be said for the proud owner of shares of American International Group (AIG) stock, assuming that you picked them up sometime in the early 1990s, and—here comes the critical part—that you sold them prior to mid-2008. You could be considered be a trading guru. However, if you bought the stock near the onset of the economic downturn and were not able to read the tea leaves properly, all else being equal, the end result was a knock to your overall net worth. Not that AIG should bear the entire burden of that example, though. Take the overwhelming majority of financial institutions and the illustration still holds.

Insurance premium trends and the economic downturn

Given those few examples, there is little doubt as to the truth of the cliché "Timing is everything." Over the last several years, I have repeatedly heard principals of insurance agencies say that the timing is just not right to sell. When I first started hearing this, the comment stemmed from the onset of the soft market. Depending upon the line of business, and assuming no new business was written, an insurance agency could have seen declines by as much 20% per annum due to the soft market.

Lately, however, the message has changed. While the soft market still persists, the more common reason not to consider selling is exposure. Given the disaster in the financial markets, the overall economic meltdown, and high unemployment rates, many agency owners have seen their revenues shrink more due to the corresponding decrease in the underlying exposure base of their clients. And that is assuming that the insured is still in business.

Declines in valuation multiples

Regardless of the rumor mill or what has "worked for you in the past," valuation in the insurance brokerage space (and in general) is based on a metric of earnings. While it may vary between parties, the most widely accepted valuation base is EBITDA, Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization.

It may be true that an insurance agency's EBITDA is not what it once was three or four years ago, given the aforementioned decline in the insurance premium market and the overall economy. However, the decline in the valuation metric, or multiple, is not an appropriate assessment of today's marketplace. The stabilization of the financial markets, which began in 2009, corresponded directly with the emergence, or re-emergence of several acquirers/aggregators.

While some firms were active from an acquisition standpoint throughout the cycle (e.g., Brown & Brown), others scaled back their activity. However, the loosening of credit, as well as other factors, led to the re-emergence of the private equity-backed brokerages (e.g., Hub International and USI Holdings). In addition, Marsh decided to enter the middle market space during this time as well, with the founding of Marsh & McLennan Agency, which has acquired well in excess of $200 million in revenues since its inception.

These are just a few examples, but the old economic theory of supply and demand applies here. Given the comments herein about agency principals' perception of the value of their agency, and given the overall economy as well as the effect of declining insurance premiums, it would be a logical conclusion that the supply of agencies for sale is lower than it once was during the most recent hard market. However, even if one assumes that it has remained constant, the demand (buying side) has increased given the loosening of credit since the financial market meltdown.

|

| |

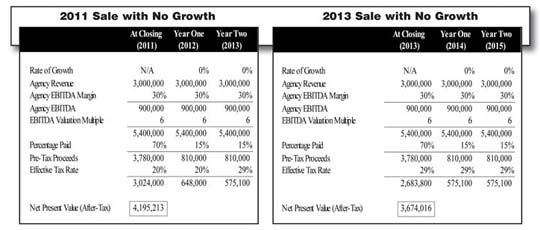

| The above charts illustrate how delaying the sale of an agency could impact after-tax proceeds. |

Capital gains rates

Last year, many agency principals entertained the thought of selling their agency due to the pending expirations of the tax cuts in the capital gains rates, which were put into effect through the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003. Among other things, this law moved the federal capital gains rate from 20% to its current 15%, but it was set to expire January 1, 2011.

During 2010, however, the political environment changed dramatically, which was most likely attributable to the overall economy, the high unemployment rates, and, one might argue, the passage of the Health Care and Reconciliation Act of 2010. The end result of this was a swing in the majority party in the United States House of Representatives. And the ultimate effect of public sentiment was a two-year extension of the current capital gains tax rates for all individuals (i.e., the federal rate is now set to maintain the current 15% rate until January 1, 2013).

One should be wary of overlooking the capital gains tax rate because it is one of the most critical factors in valuation. Ultimately, from a seller's point of view, the most important factor in considering deal price and structure is how much money winds up in your pocket once the deal is done.

Weighing the factors

As previously mentioned, these tax cuts are set to expire on January 1, 2013, when the rate will most likely return to its previous 20% level. But, as the last couple of years have reminded us, what if the world at the start of 2013 does not look like what it once did? What if we are in a period of heavy inflation? What if the projections of the Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget related to the Health Care and Reconciliation Act of 2010 do not hold, and the federal deficit becomes worse than it is in its current state? What if Congress elects not to push through the forecasted cuts in Medicare, historically a taboo subject, that are contemplated to fund a portion of the Health Care Reform bill? Where will the money come from then, and what will be the public sentiment? Will Congress be forced not only to let the capital gains tax cuts expire, but also to increase them beyond the previous 20% level? Historically, the rate has been well in excess of that level, and one could argue that overall public reaction to a rise in this rate, given its perception that capital gains taxes affect mostly the wealthy, would not result in a huge backlash to whatever administration is in power at that time.

Disregarding capital gains for a moment, when will the insurance market harden? Historically, the soft market's duration has well exceeded that experienced by hard markets. And aside from "the wind blowing" and causing catastrophic damage, the overall sentiment seems to be that a hard market is not in our near future. And if you couple that with the fact that most economists tend to point towards a long, protracted recovery in the overall economy, the exposure base does not appear to be ready to make a quick ascension either.

Timetable

Back to the notion of "timing is everything." If your timetable for monetizing your investment is within the next five to 10 years, the time to start planning your exit process is now. Not only does the process of selling your agency take time away from your agency, it takes time to accomplish.

Once an owner has decided to sell his or her firm, he or she should expect the process to take, at a minimum, six to nine months from that point forward to consummate the deal. The overwhelming majority of deals, however, will contain earn-out provisions (i.e., the balance of the purchase price not paid at closing will generally be subject to certain future performance metrics in order to receive it). These earn-out provisions will generally span a two- to three-year period. So, once an owner embarks down the road to sell the agency, he or she should expect three to four years before all the financial aspects of the deal have been finalized.

In general, the federal government allows the installment method for taxation of cash proceeds from the sale of a business, which effectively means that the seller's proceeds are taxed at the applicable rates in effect at the date of receipt. Accordingly, if your window for sale is within the next five or 10 years, and you believe that there is a risk that the capital gains tax rates will increase in 2013, then you should give consideration today as to how this would affect your after-tax proceeds (i.e., the money ultimately in your pocket).

Illustration

As previously mentioned, a portion of the purchase price is generally paid at closing, with the remaining balance being subject to risk/performance over a two- to three-year period. If we consider an owner who is contemplating selling in the next five years, the factors to weigh are: (1) what would be the effect of a change in the tax law, and (2) what would be the effect if the agency does grow or does not grow?

So, assuming that the capital gains rate does increase in 2013, the combined federal rate would increase from 15% to 20%, and for these examples, we will assume that the state capital gains rate remains constant at 5%. Also, legislation has already been enacted for a 4% (rounded) increase beginning in 2013 related to the Health Care Reform bill, so the overall rate will increase to 29% in 2013 in this illustration.

Currently, agencies are having difficulty maintaining their footing when it comes to revenues; and with no hard market in sight, the first set of examples on page XX assumes no growth during the period. The second set of examples (above) will assume annual growth of 5% per year. In all examples, the discount rate will be 3%.

In this simple example, if you assume the agency will be stagnant from now until 2015 and that the tax rates do increase, the owner will net approximately $521,000 less by waiting until 2013 to sell. On the other hand, if we were to assume that revenues increase by 5% each year for the next five years (in other words, the agency grows from $3 million to $3.65 million in annual revenues over five years), then the gap narrows in between holding and selling, but it still remains a sizeable delta at approximately $142,000 (in favor of having sold in 2011).

So, maybe Kenny Rogers did know what he was saying when he observed, "You got to know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em." And maybe there is some truth in the "Timing is everything" adage. Either way you look at it, though, if your timetable to sell is in the next five years, you would be wise to evaluate your options beginning today, as the reward for waiting for the hard market may well be eliminated or certainly mitigated by the risk of an increase in the capital gains tax rate.

The author

Kevin W. Smith is a director and co-founder of Mystic Capital Advisors Group, LLC. He can be reached at (704) 232-6643 or via e-mail at kwsmith@mysticcapital.com. For more information on Mystic Capital, visit their Web site at www.mysticcapital.com.

|

|

| |

|

| |

Will Congress be forced not only to let the capital gains tax cuts expire at the end of 2012, but also to increase them beyond the previous (pre-2003) 20% level? |

|