LEADERSHIP

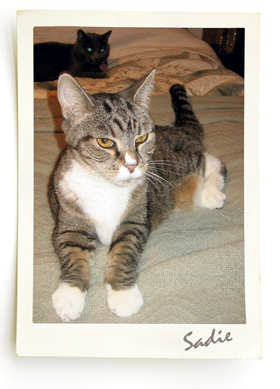

Everything changed the night Sadie came in

Sadie was not my cat. She belonged to my brother, Al, who had to let me keep her when he joined the Navy—at age 33—after 9/11. But that’s another story. Al found Sadie when she was just a few weeks old, crying under a bush near his apartment in Florida. She wasn’t ours. But we loved her, and I think she came to feel the same way about us.

Sadie loved the fact that she had five acres to run. She stayed outside so much that we set her up with a cat door, a big kennel, and food and water in the tack room. Her boy, Blackie, came to us, too, and lived with her outside. He didn’t stay with us, however. Blackie went on walkabout two months after we got him and ended up staying in a neighborhood across the street. Cats are known for having a mind of their own.

If there aren’t enough ways to keep growing your talents and you can’t find new angles at your current position to keep you happy and focused, you may drag down the rest of the team.

Back to Sadie. For many years she lived in our barn. She and Jake were fabulous mousers. She survived a raccoon attack and two weeks in our bedroom with tubes and antibiotics. Then she was right back outside through her cat door. She knew she could come into the house whenever she’d like, and she did visit every so often.

For years, most of my time with Sadie was in the morning and again in the evening, when I went to the barn to feed the horses. She always came over to visit me then; we had a routine. I think she wanted to check up on me regularly, and we had a set pattern to our visits.

One day, after a trip out of town for a few days, I went to the barn and couldn’t find her. I called and called, with no response. I was really worried. When Paul got home, I asked him if he’d seen her and he said, “She came inside the other night. Let’s look upstairs.” Sure enough, she was upstairs in the same room where she’d recovered earlier. There was always food and a litter box up there. She’d taken up residence in that room!

One day, after a trip out of town for a few days, I went to the barn and couldn’t find her. I called and called, with no response. I was really worried. When Paul got home, I asked him if he’d seen her and he said, “She came inside the other night. Let’s look upstairs.” Sure enough, she was upstairs in the same room where she’d recovered earlier. There was always food and a litter box up there. She’d taken up residence in that room!

Paul informed me that, on my first night out of town, he’d seen her streak by faster than he’d ever seen her run and she went straight upstairs. From what we could tell, she never went outside again. We never did figure out what made her want to live inside, but something very clearly told her it was time to become a house cat.

Leadership lessons

Sadie made evident the importance of having a solid “management by walking around” (MBWA) routine. Such a routine lets you know quickly when something is wrong so that you can address it. The first time she didn’t come to visit me when I was feeding the horses, I knew we might have a problem. If we hadn’t found her and treated that infection from the raccoon, she wouldn’t have survived.

Know your followers well enough to spot trouble. Walk around. Get to know them. Be a part of their everyday life, even if just for a little while. Create enough routine in everyone’s day that you are all in tune with one another. Listen, observe, and react when needed. Don’t ignore an issue until it’s a full-blown disaster. It’s your job to rock the boat if it means keeping it from running over a waterfall.

Sadie also helps us recognize one of the two hardest decisions managers have to make. One of them has to do with when to finally let an employee go—something another stray taught me. But Sadie’s story was about knowing when to quit, when to retire, when to move on from one company to the next, or from one project to another.

When is it time for you to leave, rest, retire, or just go lead a different team? How do we know when it’s time to hang ’em up? Well, the answer to that just leads to a long list of additional questions. Only you know the right answers.

It may seem obvious, but first you need to know yourself. Measure your joy each day. Figure out when you’re reluctant to get going, when you are dragging yourself into the office. Is it a phase or are you done? Do you hang on well past the point of value because it’s routine? Is your job easy for you, like “shooting fish in a barrel”?

If there aren’t enough ways to keep growing your talents and you can’t find new angles at your current position to keep you happy and focused, you may drag down the rest of the team. Either invent something new to do within your job scope or get out. It sounds harsh, but one way to know it’s right is to honestly measure the level of excitement you feel inside when you are thinking about your next move. A little fear is normal with any change.

Beyond that, are you doodling about your new plans during the current job’s meetings? Are you thinking of the name of your book? Are you outlining organizational charts for your own imaginary company? If so, it might be time for a change!

This same thinking applies to project terminations, too. When is it time to cut your losses on a particular project that just doesn’t seem to get off the ground? Can something be shelved so that resources can be used somewhere else, even if it’s temporarily? Is it time to kill the sacred cow in your shop?

The next question set involves knowing your company and its people. Where do you rank in terms of value to them? Have you stagnated? Are you really leading anymore or are you just pulling the train cars down the same track every day? Are you inspiring the future on a daily basis for them and for yourself?

Finally, examine your industry. Do you work for the last of the buggy whip manufacturers? Are the leaders above you working in reality or just riding the wave of the current trend? What can you do in the here and now to improve the possibilities of the next generation of people in your industry?

Sadie knew when to hang ’em up. We’ll never know why she decided to come inside, but we had many more years of enjoying that new adventure with her.

The author

Lisa Harrington is executive vice president and chief marketing officer at IRMI. She is the author of “Taking in Strays: Leadership Lessons from Unexpected Places,” a book from which this article was adapted. Connect with Lisa on LinkedIn or email her at lisa.h@IRMI.com.