Reliving painful childhood experiences helps others avoid—or emerge from—the darkness of childhood sexual abuse

When Walt Gdowski, owner and CEO of The Rough Notes Company, and Bob Kretzmer, executive director of The Rough Notes Company Community Service Award, conceived the idea of the award in 2000, they probably did not envision the variety of charitable services for which independent agents would be honored throughout the 17 years of its existence.

Many of these philanthropic endeavors were based on a personal component: a visit to a third-world country spawns an effort to alleviate starvation; an agent invites a friend’s grandchild who was born with cerebral palsy to ride a horse on the agent’s farm—and a therapeutic horseback riding clinic takes shape; an adult autism community living facility comes into existence because an agent’s autistic daughter has aged beyond childhood.

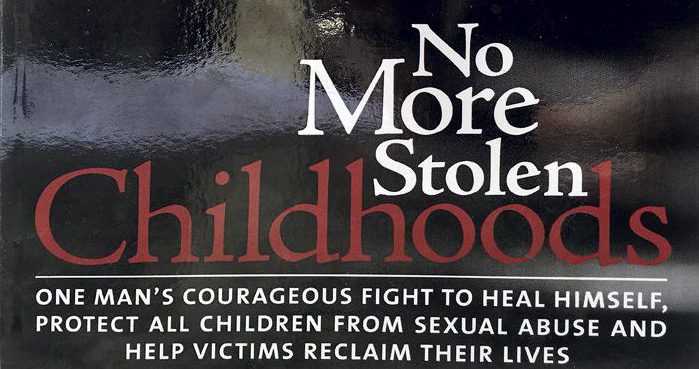

This year’s award goes to a person whose desire to give back to his community was born out of his own lifelong struggle with the aftermath of childhood sexual abuse. It has been a long struggle, which award recipient Wayne Coffey, president of Coffey & Co. in Hunt Valley, Maryland, chronicles in his short but powerful book No More Stolen Childhoods.

To ensure that young victims of sexual abuse will be able to reveal and deal with their experiences has become Wayne’s primary purpose in life. To help achieve this goal, he founded a nonprofit organization that bears the same name as the title of his book, No More Stolen Childhoods (NMSC).

During his growing-up years, two organizations helped ground Wayne, providing him with a moral compass as he struggled with his hidden life of sexual abuse. Wayne says that, in his parochial education, he found support for his faith. “I felt challenged intellectually.… [and] could push myself to my limits and excel.”

Second, his years in Scouting provided stability, as well as an opportunity to find solace in nature and an escape from the offending person. Meetings and campouts often fell on days when the family, including the abuser, got together. Most of all, however, Wayne soaked in the ideals and call to leadership that Scouting provided. A Scouting youth leadership training program taught specific leadership skills that boys were encouraged to apply at home, in the community, and, as Wayne later discovered, in their adult lives, too.

“Scouting made me feel good about myself,” he observes. “It provided ideals I could aspire to and measure myself against: self-reliance, courage, honesty, kindness, helpfulness, and loyalty. I took the Scout Oath as gospel. Even today I strive to adhere to it.”

Having believed that he had dealt with his experiences and put them behind him, Wayne did not realize that his adult explosions of temper on certain days of the week, strange reactions to particular odors, and a burning desire to be the best and achieve perfection were adult manifestations of the effects of the abuse. As a result, although he had become a successful and respected businessman; was blessed with a loving and caring wife; interacted with and doted on his children, there always were those strange reactions that seemed to have no cause.

Then, in 1998, Wayne encountered the first of two instances of what some would call a moment of serendipity and what others might refer to as a “God-thing.” At that point, his firm, Coffey & Company, was growing. “I was on top of the world professionally,” says Wayne. “Personally, however, I was imploding. Like a black hole, I was sucking my family into my continued rage.” His marriage had reached a crisis point.

Dolores, Wayne’s wife, prayed a “Hail Mary” prayer that “someone, something—anything—would step forward to help me.” The very next day, her call was answered. While driving to a meeting, Wayne was listening to a radio program during which author Dr. Dan B. Allender spoke of the fallout from abuse—“the feelings of powerlessness, unworthiness and betrayal it engenders, and how keeping abuse secret deadens the soul and negatively affects all relationships, including one’s relationship to God.”

Wayne immediately sought counseling, and decided to prosecute his abuser. His counselor helped him understand “how deeply childhood sexual abuse wounds the soul and psyche. It’s not something you get over because you’ve done counseling. The experience is who you are,” Wayne says. And, he notes, lack of trust is an issue that lasts a lifetime.

A complete realization of the impact of a lack of trust occurred during the second episode of serendipity or a “God-thing.” Dolores had sent up another “Hail Mary” when, reacting to a movie about child abuse, Wayne had become physically ill and sobbed uncontrollably. “There was no more [Dolores] could do for me. She—I—needed a miracle.”

A week later, while at a professional insurance retreat in California in 2004, Wayne and his wife visited the farm of the famous horse whisperer, Monty Roberts. Despite witnessing Monty’s breaking of a wild mustang through the use of his Join-Up method, which was based on trust rather than force, Wayne remained skeptical.

Through the sort of sixth sense that abused people seem to acquire, Monty, who by the time he was 12 had suffered 72 broken bones, intuited that Wayne was in trouble and convinced Dolores that he could help him if they came back to learn his technique.

Six months later, they returned for what proved to be a successful four-day stay. On the last day of that visit, Monty shared, “Each day I wake up a violent man. Because of my experience with my violent father, violence is imprinted on me. But I make a decision not to stay that way. Instead, I wake up each morning determined to do some good.”

At that point, back in 2004, the seeds of his not-for-profit, No More Stolen Childhoods, were planted. All that Wayne had learned in Scouting, at school, and at church crystallized: use your talents to help others.

In Wayne’s case, there was more. He was challenged also to draw upon the dark days of his childhood to accomplish that. Paraphrasing a Bible passage, he says, “Good can always come out of bad if one chooses to allow that to happen.” He could become God’s vehicle.

The result: the nonprofit— No More Stolen Childhoods—whose goal is expressed in its mission statement: “to change the public perception about childhood sexual abuse and to help those abused find fulfillment in their permanently scarred lives.”

How does the organization do it, and how does Wayne’s passion play into his business?

First, there are countrywide presentations where, despite the pain it brings him, Wayne speaks out publicly about his experiences.

There is an educational program, titled “Safe Kid Club,” which includes a coloring book—the Safe Kid Club Coloring Manual—that was carefully and artfully crafted to help children understand if and when they are being abused and, most important, what to do about it. Schools, civic organizations, sponsors, and parents are encouraged to “join in our effort to empower children to stay safe from predators,” it says.

There also is the book mentioned earlier in this article.

And, finally, there is the life-changing video, More Than Stranger Danger: Understanding the Reality of Child Molesting. As part of his campaign, Wayne invited insurance carriers into the office to share the video. Members of the staff, who also had been invited, were so stunned by Wayne’s testimony that they immediately jumped on the bandwagon.

“I’m absolutely blessed,” says Wayne, speaking of those employees who often provide administrative support to NMSC. For example, Brianne Fritze worked with the nonprofit’s executive director on a fundraising dinner that featured the video and also provided marketing materials at another fundraising event. And another employee, Katy Nash, nominated NMSC for a grant that would provide funding for the organization.

“I’m absolutely blessed,” says Wayne, speaking of those employees who often provide administrative support to NMSC. For example, Brianne Fritze worked with the nonprofit’s executive director on a fundraising dinner that featured the video and also provided marketing materials at another fundraising event. And another employee, Katy Nash, nominated NMSC for a grant that would provide funding for the organization.

In 2016 alone, Coffey & Company provided financial support for NMSC—office space, phone bill expenses, tech support, etc., to the tune of $7,136.79. Soon, according to the executive director of NMSC, Beth Hopkins, “With the partnership, committed support, and financial investment of Coffey & Co., NMSC—in conjunction with Renegade Productions—will be creating a scholarly white paper and TED-Ed lesson on childhood sexual abuse.”

If Wayne feels blessed because of the devotion of his employees, they, if asked, would probably say that they are blessed to work at his agency. Committed to “changing the perception—and reality—of the insurance agency system,” Wayne operates under three core principles: integrity, professionalism and competence, all an outgrowth of the formative childhood experiences that were in direct contrast to the abuse he had suffered.

To sum it all up, Wayne says, “I will never say, ‘Oh, woe is me.’ I can overcome and live a life that is giving back. To share is to relive and it is painful. It’s difficult at times, and I need an occasional break. I can’t do it full time.” The “breaks” are made up of, first, his family, second, his business, and then myriad community activities.

By Alice Ashby Roettger

For more information:

No More Stolen Childhoods